By Joe Kearns

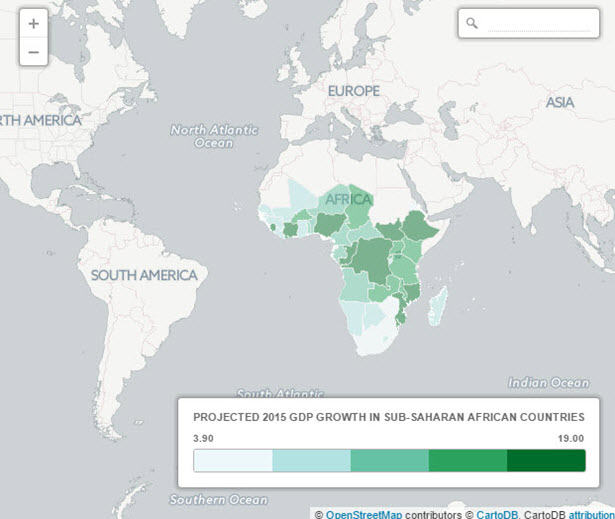

Africa has long been, and largely still is, avoided like the plague by investors from developed economies due to concerns over government corruption, war, and poor infrastructure. It shouldn’t be. Though declining commodity prices, China’s economic downturn, and policy failures have eroded investor confidence in Africa, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects the continent’s economic growth to reach 4% in 2016, a modest increase from 3.5% in 2015. In contrast, 2015 World GDP growth was -0.4% and U.S. GDP growth was 0.0%. The rational action for investors in developed economies searching for positive returns is to jump on a largely untapped opportunity to invest in Africa and go against the conventional bearish sentiment.

The bedrock assumption of classical economics that individuals make rational choices is challenged by a concept in international finance called the equity home bias puzzle. Financial economist Kenneth French and public economist James Poterba wrote in “Investor Diversification and International Equity Markets” (1991) that individuals and institutions in most countries predominantly hold domestic equity and only a marginal amount of foreign equity. According to French and Poterba, at “the end of 1989, Japanese investors had only 1.9% of their equity in foreign stocks, while U.S. investors held 6.2% of their equity portfolio overseas.” In December 2014, David Snowball, publisher of the Mutual Fund Observer newsletter, estimated that just 0.3% of the average portfolio in the United States, or $3 of every $1000, is invested in African assets.

It is true that many African investments have not fared well recently. Nigeria’s stock market index is down by 16% since the start of 2016. The S&P Zambia Index plunged 45% and its currency, the kwacha, depreciated by 45% relative to the dollar in one year. Ghana became mired in an economic crisis and had to pay a steep 10.75% interest rate for $1 billion in Eurobond. But even amidst unfavorable economic circumstances, the Ivory Coast stock exchange gained 7% in 2015 and the Kenyan stock exchange has been in the black since January. Both the Ivory Coast and Kenya are energy importers that benefit from the very phenomena which hurt economies like Angola, Nigeria, and Equatorial Guinea for whom 90% of export revenue is accounted for by oil.

It hardly seems rational for investors—even risk-averse investors—to invest so little in such a promising opportunity. It is best not to look at Africa as a monolithic entity, but a variety of economies with their own unique investment opportunities that fare differently over time. There are several reasons to remain optimistic about the future of Africa and the recent dip in African stocks and currencies means now is an excellent time to join the party.

Why Will African Economies Outperform the Developed World?

Demographics suggest that Africa is attaining a labor market which is conducive to strong economic growth. Africa has the youngest population in the world with 200 million people aged between 15 and 24. According to the United Nations, this figure will double to 400 million people by 2045.

It should be stressed that the economic situation is far from completely rosy in Africa. Six of the ten fastest growing economies in the world are in Sub-Saharan Africa, but the unemployment rate for the region is 6%. The African Development Bank (AfDB) reports that regional youth unemployment is twice as high as the general unemployment rate. North Africa especially suffers from high youth unemployment with a youth unemployment rate at 30%. Botswana, the Republic of the Congo, Senegal, and South Africa are among the countries which fare even worse than that region.

Nevertheless, Marketwatch reporter Sara Sjolin conveyed a valid reason to believe the labor market will improve: “In the strongest African economies, as the workforce expands, economists expect demographics to drive higher demand for services, goods, housing and infrastructure, which in turn will help drive domestic economies.”

To make this happen, African policymakers need to shift government spending towards facilitating growth in sectors like agriculture and manufacturing. Thomas Vester, manager of $875 million at the LGM Frontier Markets fund, credited Kenya, Ghana, Botswana, and Zambia as countries which have recently committed to longer-term projects like infrastructure and housing construction to support sectors with strong future growth. Vester forecasts that these economies will experience a 20-year trend of growth of about 6%-7% due to the fiscal stimulus. African policymakers have recognized that the optimal role of government is to intervene to facilitate economic growth and are slowly beginning to reap the rewards.

Most importantly, data suggests that Africa is undergoing a transformative moment in its economic history. The natural resources and mining sectors have been the fastest-growing sectors for years in Africa, but Sjolin argues, “With rapid economic growth also comes a rising middle class that wants to go out, open bank accounts, buy branded groceries and, eventually, buy cars, houses and life insurance.” The biggest African economy, Nigeria, saw its middle class grow by 600% between 2000 and 2014. Sjolin also believes that by 2030 Ghana, Angola, and Sudan will experience a steep increase in middle-class families as well.

The growth of a large middle class will be vital for African economic growth. Middle class consumers have a high marginal propensity to consume relative to their upper class counterparts, but also more disposable income than the poor. For this reason, the forecast of a substantially expanded middle class is the biggest reason to be optimistic about African economic growth.

What Are The Best Investment Opportunities in Africa?

The question for investors is who benefits from the consumption patterns of the new African middle class. Vester indicates that these middle-class consumers are likely to boost profitability for telecom companies, food and beverage companies, and banks. His fund has holdings in companies like the Guaranty Trust Bank in Nigeria and Senegalese telecom provider Sonatel. Meanwhile, Mark Mobius, executive chairman of Templeton Emerging Markets Group and manager of the Templeton Africa Fund, owns holdings Guaranty Trust Bank as well, along with Zenith Bank (Nigeria), Nigerian Breweries (Nigeria), and telecom firm MTN Group (South Africa).

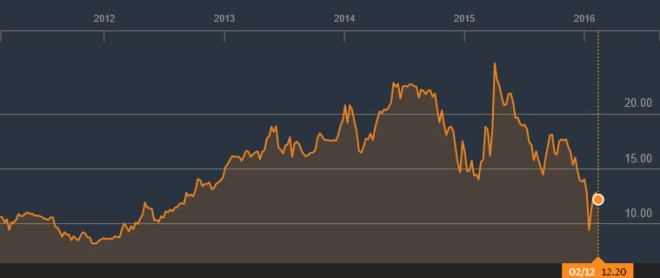

Vester and Mobius, however, entered into long positions with these firms at the end of 2014, prior to the volatility of 2015 and the asset market plunge in 2016. Consequently, the stock prices for companies have recently plummeted as shown below:

Guaranty Trust Bank PLC

Zenith Bank PLC

Nigerian Breweries PLC

MTN Group PLC

These companies have seen sharp dips in their market value in the past year, but there are reasons to be confident in their fundamentals.

These companies have seen sharp dips in their market value in the past year, but there are reasons to be confident in their fundamentals.

This small sample shows that it is reasonable to believe that there are long-term opportunities to invest in Africa and earn a high return. Though investors are afraid of the macroeconomic outlook in the short term, financial analysis of these companies indicates these fears are misdirected. The relatively high earnings per share, along with the relatively low price/sales and price/earnings (Nigerian Breweries PLC excepted for the P/E pattern), indicates that African companies can be solid bargains.

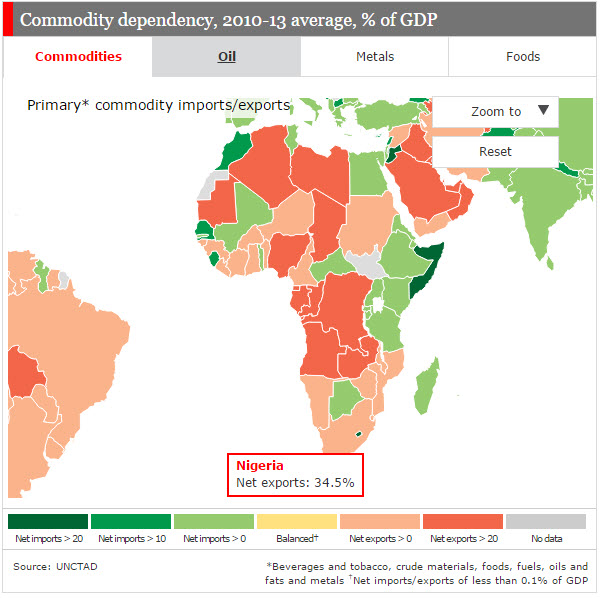

With that being said, it is rational for short-term investors to have some anxiety. Like many frontier markets, African economies have struggled because of monetary policy divergence with the Federal Reserve Bank of the United States which has begun to raise its benchmark interest rate. More significantly, however, many African economies are dependent on exporting commodities like brent crude, foods, and metals. For instance, Nigeria’s net exports of commodities consist of 34.5% of its GDP.

For the time being, many African countries—especially the ones shaded in dark red on the graphic from The Economist shown above—are vulnerable to price swings of commodities like the drop in brent crude from $104.90 to its current level of $32.70. But given the fact that African governments have begun to diversify their economies, it is reasonable to believe that the woes of African stocks are transitory. If the map above looks much different in twenty years as I suspect, that means assets in Africa will have increased in value exponentially from where they are now. It is a risk to make that assumption, but I believe it is a well-calculated risk.

The Future

The long-term potential of African economic growth has created an excellent opportunity to exploit the risk aversion of other investors. There are short-term pains now, but it is best to follow the advice of Laura Garitz, manager of the U.S.-based Wasatch Frontier Emerging Small Countries fund. One quarter of her fund’s assets are invested in Africa and she has made no reductions this year. “Africa’s countries can no longer depend on a booming export market for resources to China,” Ms. Geritz said to The Wall Street Journal. “Africa will have to depend on its greatest asset—it’s pool of young, bright, driven people.”

Moreover, the equity home bias puzzle demonstrates the validity of contributions from behavioral finance. There are not many fundamental reasons investors should allocate almost all of their assets in their home country, which creates an opportunity for risk-seeking investors willing to look elsewhere. Data indicates that Africa is clearly the best region for these investors to earn a high return. By continuing to miss out on the vast economic growth from the continent, developed market investors are leaving easy money on the table. Simply put, it pays to not always root for the home team.

Author’s Note: As always, this post reflects solely my own views, not those of the Penn State Economics Association or any other entity I represent.